Spotify is the digital equivalent of smearing shit on a musician’s face.

Right, now that I’ve cleared up my position on the matter, allow me to explain what’s going on.

Background to Bandcamp Vs Spotify

With the release of The End under my own name, I upgraded my Amuse account to the Pro version. It’s $60 per year.

Now, I’ve been recording and releasing music for much longer than I’ve been doing Light Audio Recording. Initially, back when I wanted to be a rock star, I paid TuneCore a wad of cash to get my music on iTunes back in the day, and whatever other streaming platforms.

But, it was expensive. I can’t remember the specifics, but I was spending money on every release. Eventually, I realized that:

- Making money back from digital music distribution was only worth a damn if you had the marketing capabilities of a major label

- Selling music to people on CD, at your gig, while you were playing a set was far more effective; seriously – we made more money with cassettes than we ever did by any digital means

Eventually, I sacked all that off for Bandcamp, which suited much better:

- People could listen to the songs and buy them if they like them

- There was no upfront cost to me; Bandcamp takes a cut for the service they provide when money is made; that’s much fairer on musicians who don’t start off rich

There were other reasons I liked Bandcamp, but for the purposes of this narrative, those are the points I’ll focus on.

Of course, mostly the only people who know and use Bandcamp are musicians. Sadly, everybody uses Spotify. Nobody is interested enough in self-released music to give a monkey’s about another music platform just to hear their mate’s band.

The only way people will listen to their music is through a platform they have to pay a wad of cash to be on that they won’t make back.

Things change

With Light Audio Recording, I was initially hesitant about releasing music on Spotify. But, when I found Amuse, there seemed no harm in adding a little additional residual income, however little it would be.

For context, the minimum for a payout from Amuse is $10. I currently have $0.41.

When I decided to do all I did with The End, I opted to pay the $60 to upgrade rather than set up a new account so I could release it for free. I figured there was no harm in having an option for releasing music under different names. Also it didn’t occur to me that I could have just used a different email address.

Eventually, with my flat rate paid for the year, and the ability to release music under an unlimited number of projects, I started thinking about releasing older songs. Recent comments by this bell end suggest that quantity rather than quality is what Spotify is about.

And, ultimately, hateful enough as the platform is, why shouldn’t I try and make a buck? It’s not costing anything extra to do so, but it’ll still take 2,000 plays. Between Light Audio Recording songs and The End, I currently have a total of 85 plays.

So began the process of adding all these old songs to Spotify via Amuse.

At the time of writing, I have four releases done. The process is interesting. I noted and learned a few things that I didn’t know before. I thought it might be useful to document them, because I’m sure I’m not the first, and definitely not the last to look at these things.

As long as Amuse continues to expand, and its competitors appear, and digital music distribution become increasingly democratized and accessible, well…

What I learned about putting your music that’s released on Bandcamp onto Spotify and other contemporary mainstream platforms

The music

Firstly, I didn’t have all the songs from previous projects in one place.

There are some on Dropbox, some on Google Drive, and some on external drives at my parents’ house in Ireland. So that’s an awkward starting point.

Even when I found some, they were MP3s. I needed the WAVs used for their original release.

In fact, the only place I definitely knew of that had the WAV files for releases was on Bandcamp itself! I quickly Googled if I could retrieve them, and it looks like I’m not the first person with this query!

This article explained: I had to turn off any pricing and download them, as if I was buying them. It’s a fiddle, but nice to know it could be done.

I started off by downloading Nerve Centre’s first EP, The Droids You’re Looking For.

Samples and covers

While thinking about uploading Nerve Centre’s music, it occurred to me that a few of them had samples from real songs. There was also at least one cover as a hidden track. And I sure as shit don’t have the money to get them cleared!

I didn’t remember being asked about it in uploading to Bandcamp. Not even a check box. And there hadn’t been any consequences.

But, I remembered two things for sure about uploading to Amuse:

- There’s a checkbox to promise that you cleared anything that’s not orginally yours

- They have a review process, where such things can get caught

At this point, I needed to decide whether to include the albums containing problematic songs at all – or should I upload them without the offending works?

I think that was the first noticeable difference with Bandcamp. Because with Bandcamp, you upload it yourself and it’s directly on sale right away, there’s no checks for stuff like this.

Images

One of the the first things Amuse asks for is the artwork for the release. No problemo! It downloaded with the EP from Bandcamp.

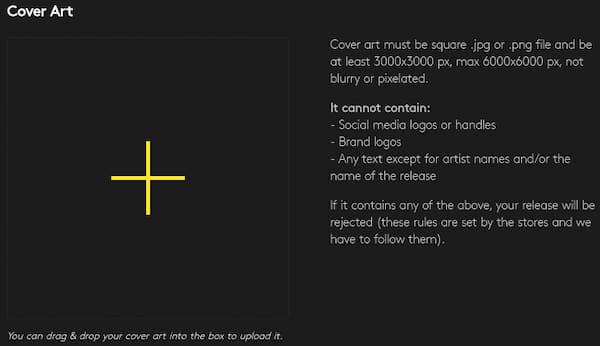

Except, Amuse specify that it should be a minimum of 3000px x 3000px in size.

What I downloaded was only 1200px by 1200px. *sigh*

How would I increase the size of an image without losing resolution? Of course, the first result in Google said Photoshop, but I have a Chromebook and not enough money. Then it said GIMP would do it.

Oh. I recently added a Linux terminal to my Chromebook. I could probably add GIMP. So, after finding a tutorial, I went ahead and installed GIMP. Then I went to a different tutorial about how to increase the size of an image without losing resolution. Then, the setting it said would do that wasn’t appearing. So, I Google that, which led me to the new name of the setting I was looking for, and hurrah! It worked!

I got that EP uploaded. However, a little later on, there was another image-related pickle.

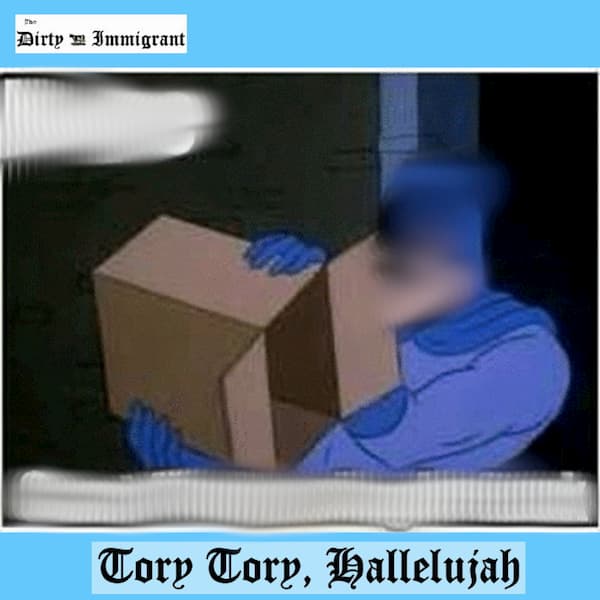

I went to upload an EP I released under the name, The Dirty Immigrant. When I went to upload the artwork for that, I noticed another direction on Amuse. The only text allowed was the artist and release name.

This EP had a whole load of Lorem Ipsum copy. What was I supposed to do? Well, I took the image back to GIMP, and I blurred it out.

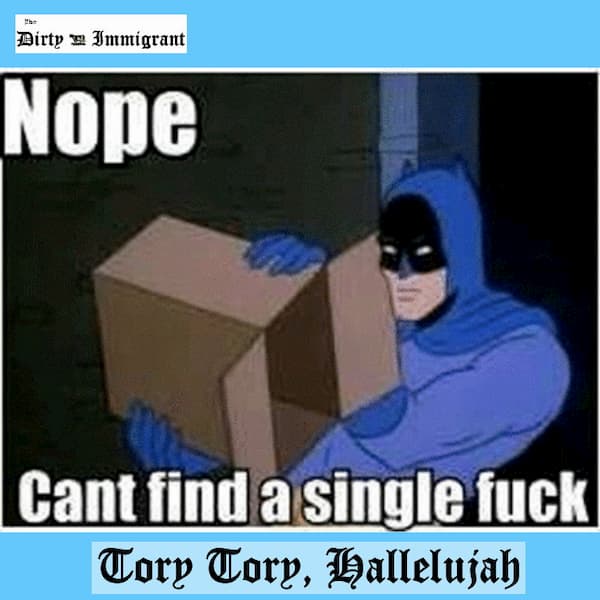

Just today, I was uploading The Dirty Immigrant’s only other release. It features a Batman meme, and I didn’t think that would fly with the good folks at Amuse. Soooo…

Special characters in release titles

I’m uploading the Nerve Centre catalog in release order. Next up was the full-length album, …And All I Got Was These…

The first thing Amuse asks for in the upload process is the release title. So, of course, like I’ve done since it was conceived and released, I just went ahead and typed in “…And All I Got Was These…“

Computer said no.

A red-fonted notice appeared, advising that release titles can’t contain special characters. I deleted those elipses at either end. The computer didn’t complain any more.

It was mildly annoying. The ellipses were included to show that it was part of a longer sentence. I can’t remember what the sentence was, but it was long and rude. That’s why it was just that short section of the sentence that was the title.

The ellipses were to indicate that there was more to the title that what could be seen. But Spotify has no time for artistic intention in release titles.

IRSC codes

Uploading The Droids You’re Looking For, the next oddity I encountered was for the ISRC code.

I know this is a thing that’s normally automatically added through music aggregators, like Tunecore and Amuse, when you don’t have one.

I went over to Bandcamp to see if I could get that for the songs I was uploading, and learned that they don’t issue any! Wait, what? Does that mean releases on Bandcamp aren’t really released at all?

It was NBD though. This was originally released through Tunecore, so I got them from there.

An interesting thing about The Droids You’re Looking For: when it first came out digitally, the song Self Confessed wasn’t recorded yet. It was on the physical release later on, and then on the digital version on Bandcamp.

I forgot about all of this until now. When Amuse asked for an ISRC code, I just skipped it.

Then, it asked…

I checked “yes”, and then it yelled at me! In red writing, a notice appeared that re-releases all needed ISRC codes. I had no choice but to replicate that original digital release, without Self Confessed.

When it came to uploading …And All I Got Was These… – or And All I Got Was These, as it’s now known – the album contains all the songs from The Droids You’re Looking For. In copying the ISRC codes from Tunecore, it turned out that they had different ISRC codes. I learned this because Amuse told me that I couldn’t use different codes for songs I’d already submitted to them.

Luckily, the alert that appeared showed the code that I used before, and I could copy and paste it.

Faffing aside, it means that Bandcamp-only releases will be regarded as brand new releases, rather than re-releases.

Royalty splits

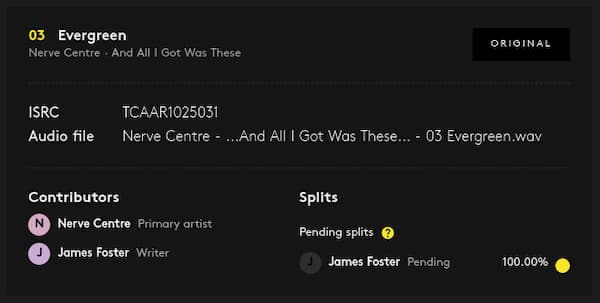

Finally, Amuse lets you arrange royalty splits directly as you need. For example, on …And All I Got Was These…, the song Evergreen was written by Nerve Centre’s lead guitarist. I could set it so that James will receive the appropriate royalty for that.

Putting your Bandcamp releases onto Spotify and other contemporary mainstream platforms: conclusion

And that’s where I’m at. I have four releases under review at Amuse.

It’s been an interesting process so far. It highlights the distinctions between Bandcamp and Spotify et al from a technical perspective.

Bandcamp is a true artists’ playground. The lack of any checks for legal stuff makes it a total playground, even in the face of gently illegal things. For example:

- Album artwork doesn’t have any real restriction

- Samples and covers don’t have any real restriction

- Release titles can have any special characters you want

- They don’t issue ISRC codes, so you can put whatever you want on whatever album

Seriously. You just put up whatever you want, and it’s there. It really is the digital equivalent of slapping together whatever you want on a CD, and selling it in the pub. There’s an artistic and creative freedom there that’s wonderful!

Spotify is just like, the man.

You follow their rules. You curb your creative and artistic intention. It’s perceived as success. And in real terms, the reward is pitiful.

*sigh*

Thanks for reading!

If you found this helpful, subscribe on the right-hand side of this page. You’ll be notified of new posts on Thursdays, inspiring you going into the weekend.

And share why you found it helpful. Because it helps us, and others!

Share your own light audio recording thoughts and experiences! There’s a Facebook group, a Subreddit, Twitter, and Instagram.

Also, on LinkedIn, you can see the business-brain of Light Audio Recording at work.

Finally, this is a music project, so we’re on Spotify – the playlist below starts with the most recent release and works backward. So, feel free to follow us!

However, do remember that it takes 2,000 plays on Spotify to generate a single dollar, so it would take 6,000 plays to get a coffee…